Drag racers—especially during the sport’s early and less restrictive years–would try anything that made sense. And not surprisingly, they looked in all sorts of places to find them.

Drag racers—especially during the sport’s early and less restrictive years–would try anything that made sense. And not surprisingly, they looked in all sorts of places to find them.

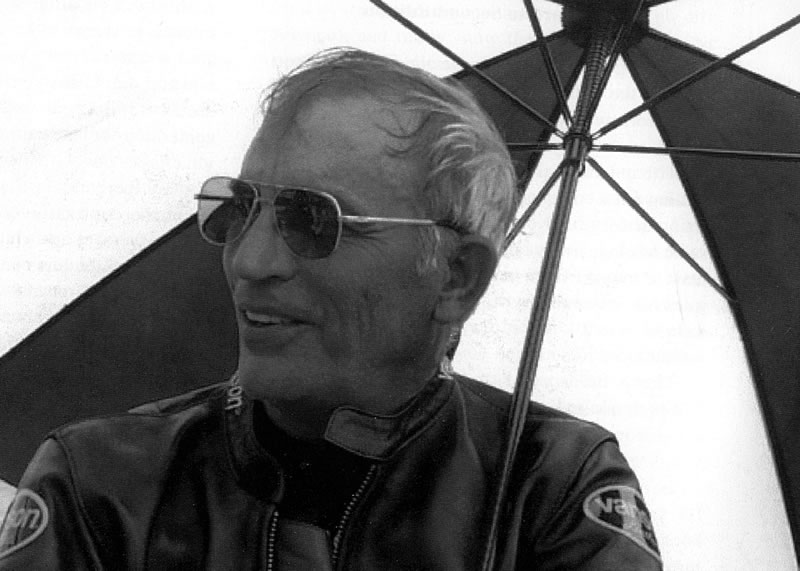

While motorcycle guys have often borrowed technology from car guys, some have gone so far as to borrow engines. And no one has been more associated with this than E.J. Potter, affectionately known as the “Michigan Madman”.

As Gary Werner, owner of a Potter machine, described him, “E.J. wasn’t your mom’s kind of role model but he was mine. He roamed the country putting on his thrill, noise and smoke show. He defied reason by not getting killed on his two-wheeled rodeo bull of a ride, and probably got paid more than most dragster drivers for the excitement he provided.”

Potter grew up in the central Michigan town of Ithaca, the son of a scientist. After first competing on dirt tracks, he decided in 1960 to pursue a dream he had sketched in his high school notebooks. The dream, of course, was putting a Chevy V-8 engine into a motorcycle frame.

“Ignorance is a powerful tool if applied at the right time, even usually surpassing knowledge.”–E.J. Potter

Although most thought the idea absurd, Potter didn’t. “My tape measure applied to the car engine told me that such a thing was not much bigger than a Harley engine, only longer,” he recalled, “and I set about finding a Harley frame to start butchering on.”

At Potter’s first race with the machine, Art Arfons was also there with his Allison-powered car “Green Monster”.

Although Potter’s machine started easily enough, problems quickly ended his day.

“I was sitting in the pit area surrounded by the remains,” he says, “when for the 187th time that day, some guy I had never seen before came up and started looking the thing over. Being submerged in the depths of dejection, I naturally didn’t make much of an effort to be sociable. He didn’t say much at all, except that it looked to him like I could eventually make some money with that bike if I would stick to it until I had the bugs out. He walked on to the other end of the pits and the crew came running up wanting to know what he had said. I made some noncommittal response and said, “Why, who was it?” Art Arfons. Well, I guess you know how that little tidbit of news made me feel after I, shall we say, had just passed up the chance to talk to the King and really find stuff out.”

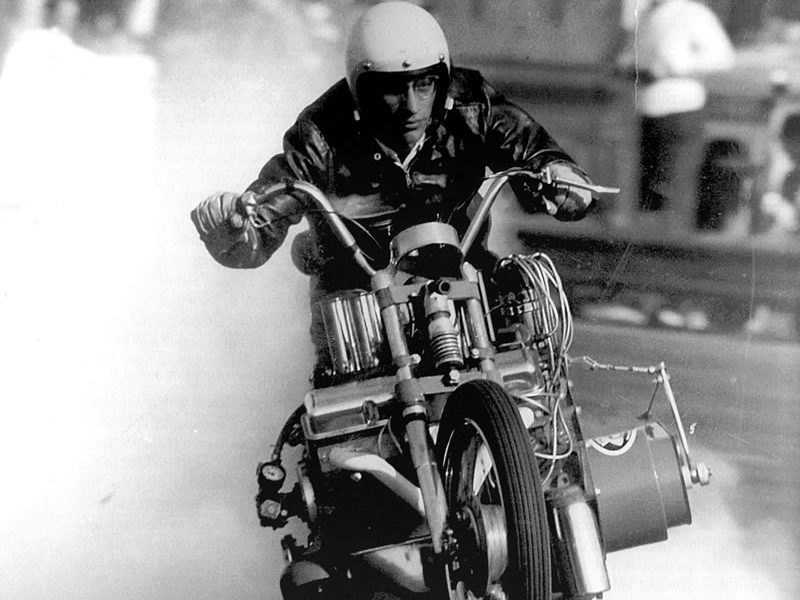

Encouraged, Potter would spend more than a decade building, racing–and sometimes wrecking–six more “Widowmaker” machines. And he did so throughout the world–the fans in England, Australia and Canada as enthusiastic as those in the U.S.

Because of their enthusiasm and the effect it had on promoters, Potter was paid $1 for every mile per hour he exceeded 100 mph. He quickly realized that his homemade clutch (built from a Harley-Davidson drum brake) was limiting his maximum trap speed to about 115 mph and that, in turn, limited his income to no more than $15 per race. His solution–and Potter always found one–was to eliminate the clutch altogether. As a result of his new “direct-drive” arrangement, trap speeds increased to 136 mph and the promoter was forced to renegotiate.

Because of their enthusiasm and the effect it had on promoters, Potter was paid $1 for every mile per hour he exceeded 100 mph. He quickly realized that his homemade clutch (built from a Harley-Davidson drum brake) was limiting his maximum trap speed to about 115 mph and that, in turn, limited his income to no more than $15 per race. His solution–and Potter always found one–was to eliminate the clutch altogether. As a result of his new “direct-drive” arrangement, trap speeds increased to 136 mph and the promoter was forced to renegotiate.

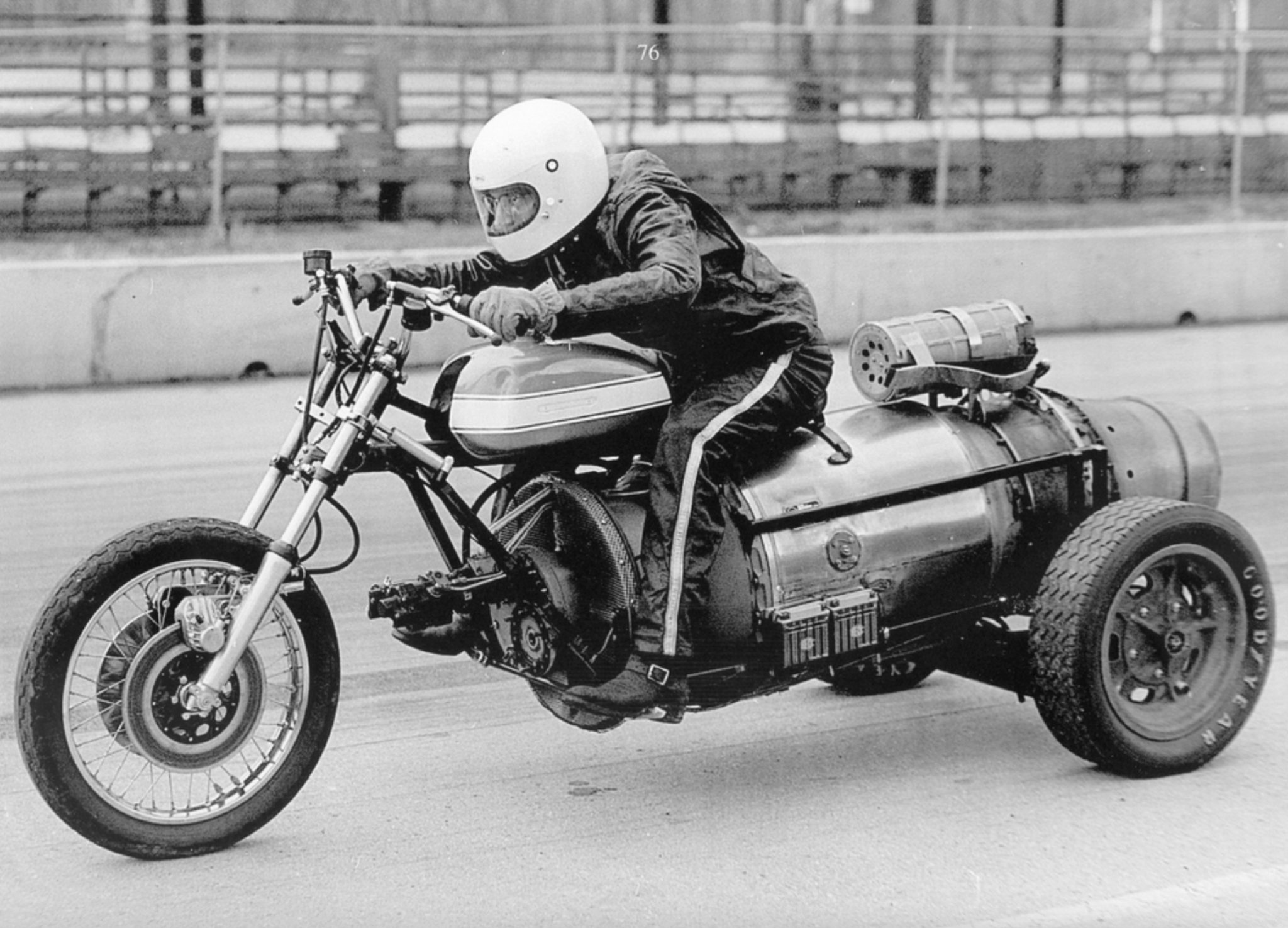

The engine Potter used was a 327 cubic inch, fuel-injected Chevrolet running on a mixture of alcohol and water, although at various times he experimented with ether and benzene. The transmission was connected to the engine by means of a chain, which was then connected to the rear sprocket by more chain.

Rather than continuing with the full-cradle design of the Harley-Davidson frame, Potter chose a large, tubular backbone and trellis configuration that used the engine as a stressed member. The rear sub-frame was un-sprung, while the front end used an Indian-Enfield telescopic fork. Rear tire was 6.70 by 15 inches and lasted three runs.

Weight of the machine was 750 pounds with Potter on board, which made for an eventful ride. In fact, he said, “In order to be worth money to a promoter, people have to think you almost got killed. That way, they buy a ticket next time.”

Although Potter’s times and speeds were competitive, they didn’t really matter. “What does matter,” said one observer, “is that his bike is a monster, awesome just to gaze at, spectacular in action, and as tricky as a wild bronco to ride.”

E.J. Potter was a builder, a mechanic, a doer and quite a showman, too, willing to build things to see if they work, willing to solve the problems, willing to give it a try, no matter how improbable the odds. We could use a few more guys like that right now.

The legendary innovator passed away in May of 2012.

Rest in Peace, E.J.