While evolution implies a continual movement in one forward direction, it can mean returning to where you began if that proves better—which is exactly what happened with Top Fuel motorcycles.

When Marion Owens’ twin-engine Harley-Davidson didn’t win at Bowling Green in 1978, it marked a changing of the guard. Multiple engines were no longer a guarantee of victory. The days of the double-engine big twin were over, and single-engine, supercharged Japanese bikes had been handed the baton. The first person to hold it was a well-to-do furniture manufacturer from Southern California named Ron Teson.

Unlike so many others who entered the sport at an early age, Teson did just the opposite. He was 28-years-old before he ever rode a motorcycle.

“When I saw the new Honda CB750,” he recalls, “I knew I had to have one of those. I ended up riding it everywhere.”

One of the places Teson rode was to a local doughnut shop, where he struck up a conversation with another motorcyclist. Carl Morrow, owner of Carl’s Speed Shop and an acclaimed Harley-Davidson tuner, challenged Teson to a race on an abandoned street. Morrow was on a tweaked Sportster that belonged to a customer; Teson was on his stock Honda 750. Morrow won the first race and Teson won the second.

The Honda didn’t remain stock for long. They rarely did.

“We put in oversize pistons from a Honda 350 which got the displacement up to 836cc,” said Teson. “Later, we made it up to 970cc. Jerry Magnuson got us one of his blowers, Hilborn supplied us with an injector for the alcohol, and the folks at Kosman built us a frame.”

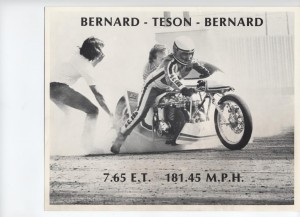

In its 1100cc configuration the Top Fuel Honda would go on to make an incredible 41, seven-second runs including an NHRA record, 7.65-second/187 mph pass.

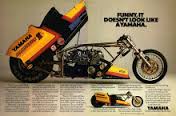

Believing that he had taken the machine as far as he could, Teson felt it was time to move on to something else. That, in turn, would require money and that would  require sponsorship. Fortunately, Russ Collins introduced Teson to people at Yamaha who gave him an XS Eleven street bike that was being used for magazine tests. The engine would be the basis for a new top Fuel machine.

require sponsorship. Fortunately, Russ Collins introduced Teson to people at Yamaha who gave him an XS Eleven street bike that was being used for magazine tests. The engine would be the basis for a new top Fuel machine.

“When you start that big, you leave room for huge.”–Gordon Jennings, Cycle

Not only was the Yamaha engine a rather substantial 1102 cc, it had a one-piece crankshaft and automotive-type connecting rods which were well suited for drag racing.

“Furthermore,” said “Cycle” magazine’s Gordon Jennings, “the engine was strong and fairly light for its displacement, and there was every indication that its considerable stock output would amplify marvelously well under the urgings of a supercharger and oxygen-bearing fuel.”

“Furthermore,” said “Cycle” magazine’s Gordon Jennings, “the engine was strong and fairly light for its displacement, and there was every indication that its considerable stock output would amplify marvelously well under the urgings of a supercharger and oxygen-bearing fuel.”

One of the challenges in adapting the engine involved the transmission. Since neither a stock transmission nor shaft drive could handle the power output, the Yamaha’s transmission was sawed off and a B&J two-speed and Dixon centrifugal clutch installed.

With that solved it was on to another area that needed it. Since the stock engine ran “backwards” in order to accommodate the shaft drive, two enormous reduction gears were required to mate the crankshaft to the drive line components.

With that solved it was on to another area that needed it. Since the stock engine ran “backwards” in order to accommodate the shaft drive, two enormous reduction gears were required to mate the crankshaft to the drive line components.

The chassis was fabricated of chrome moly steel by Kosman Specialties, while the body was made of carbon fiber with help from local boat builders. Front forks were Ceriani.

While Teson was comfortable building machines, he would become less comfortable riding them. At Orange County International Raceway, Teson fell off at 145 mph during a speed wobble. While racing in Ohio the machine became airborne while traveling 169 mph.

As he recalls, “There were no guardrails and I was in the dirt. Eventually, I got it back on track. When I finally got it stopped, I looked up to see Ray Price just standing there shaking his head from side to side.”

As he recalls, “There were no guardrails and I was in the dirt. Eventually, I got it back on track. When I finally got it stopped, I looked up to see Ray Price just standing there shaking his head from side to side.”

And so, Teson asked friend and former partner Bill Bernard if his brother Jim would be interested in riding the machine. He was, and “Teson” became “Teson and Bernard”.

In 1979, they dominated. At the Winston World Finals, Bernard faced previous year’s winner Russ Collins, top qualifier Bo O’Brochta, Suzuki-mounted Terry Vance and “Frog” Thacker (who had defeated Bernard the previous month at the NHRA Nationals). Bernard won the meet and with it the Number One plate.

Unlike so many top tuners, Teson didn’t have a motorcycle shop and was one of the few not even in the business. In fact, he was a very successful furniture manufacturer.

“Drag racing was fun but we never made any money doing it,” he recalls. “That’s ok. We weren’t in it to make money.”

He may not have made money but he did make records, with a best of 7.46 seconds and 196 mph. Just as importantly the Teson and Bernard machine set the standards for those that would follow in Top Fuel Motorcycle A new paradigm had been established. It would be up to others to advance it.

This historic machine, by the way, is for sale. Contact john@gearheadpublishing.com for details.

To learn more about the history of

the sport, you can purchase John’s book “Motorcycle Drag Racing:

A History”. Either go to gearheadpublishing.com or call

(310) 459-7542. The price is $40 and shipping is free.

Thanks for the great article as my uncle is Ron Teson and my dad (and Ron’s older brother) joined his ‘pit crew’ in the 70’s. My brother and I grew up on the Orange County Racetrack and little did we know we were actually watching motorcycle history in the making. I wouldn’t trade those days for anything.